Workplace conflicts are a natural part of organisations. Wherever people interact, there is at least potential for conflict. The longer people interact, and the more people they interact with, the higher the chance of some conflict arising. Indeed, sometimes we don’t even need other people to have a conflict with – a conflict with ourselves isn’t that rare after all.

Since conflicts won’t be going away anytime soon, we would like to support you to better:

- Understand conflict

- Resolve conflict

- Prevent conflict

But before we dive into those three topics, let’s look at what we mean by conflict, and how to structure different kinds of conflict.

What Do We Mean by Conflict?

There are many different definitions for conflicts, and reasonable people can disagree on which one fits best. For the purposes of this article, we will take conflicts to mean:

“A struggle that results when one individual’s concerns or needs are hurt by someone else; or are different from someone else’s needs or concerns.”

Crucially, this does not necessarily mean that you shout at each other to have a conflict. Conflicts can be resolved or dealt with entirely amicably. So, a conflict is not defined by the way it is handled, but by the underlying situation.

Not All Conflicts Are Equal

A helpful way to structure the topic of workplace conflicts is a simple 2×2 matrix:

- Productive vs unproductive conflicts

- Person-based vs position-based conflicts

A good question to check if your conflict is a (potentially) productive one is:

“Would we be more or less productive/innovative/efficient/etc. if we did not have this tension?”

Conflicts are productive if having them helps us better attain organisational objectives. If preventing a conflict helps achieve those objectives, it would be an unproductive conflict.

- Person-based conflicts arise from interpersonal differences.

- Position-based conflicts arise from interactions between roles or positions.

Understanding Conflicts: The Role of Biases

Our brain isn’t perfect. It uses shortcuts and pattern recognition to handle complexity. These cognitive biases help us survive, but they can also lead to misjudgments that spark or intensify conflicts.

Let’s look at three common biases:

1. Fundamental Attribution Error

We tend to attribute other people’s negative behavior to their character, but our own to circumstances.

Example: If someone cuts you off in traffic, they’re an idiot. If you do it, it was because you were in a hurry or didn’t see them.

This bias prevents us from giving others the benefit of the doubt, setting the stage for conflict.

2. Egocentric Bias

We assume others see the world like we do. But everyone has a different perspective based on their experience.

Example: You feel disrespected at work, assuming the other person shares your definition of respect. In reality, their definition may be very different.

3. Ingroup-Outgroup Bias

We’re more generous toward those we perceive as part of our group, and more critical of outsiders.

Example: We excuse poor behavior from a teammate but are less forgiving when someone from another department does the same thing.

Preventing and Resolving Conflicts: Reducing the Impact of Bias

Biases don’t always make us wrong—but they do skew our perception. Awareness helps. Next time someone triggers you, pause and ask:

- “What could be another explanation?”

- “How did the situation look from their side?”

- “What might I be missing here?”

Use open-ended questions like:

- “Help me understand how you got to that conclusion.”

- “What happened that you reacted this way?”

- “What would you have done in my place?”

These help open up dialogue and prevent escalation.

Social Needs and Conflict: The SCARF Model

If it’s not bias, what else triggers conflict? Often, it’s a threat to our social needs. Our bodies respond to social threats much like physical ones: with stress, tension, and emotional reactivity.

Biological Threat Response

Our stress response evolved to help us survive physical danger. The problem? It now reacts to social threats in the same way.

Increased heart rate, shallow breathing, reduced reasoning capacity—not great for conflict resolution.

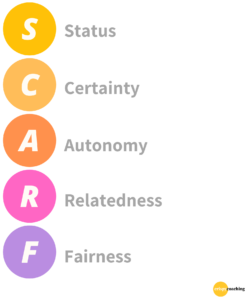

As social beings, we are wired to fear exclusion. SCARF captures our five core social needs:

- Status: Relative importance to others

- Certainty: Ability to predict the future

- Autonomy: Control over events

- Relatedness: Sense of belonging and safety

- Fairness: Perception of fair exchanges

Real-World Triggers

- Status: Receiving critical feedback from someone junior to you.

- Certainty: Being unclear about your role after a reorganisation.

- Autonomy: Being micromanaged.

- Relatedness: Feeling excluded from team bonding.

- Fairness: Unequal application of rules or credit.

Telling someone to “calm down” or “not take it personally” doesn’t help. Just as hunger is a legitimate signal, so is social pain. It helps to see these as pre-rational responses rather than irrational ones.

Resolving and Preventing Conflict: Meeting the Need

To resolve a conflict, address the underlying social need:

- Status: Give recognition, feedback, responsibility.

- Certainty: Offer clarity, roadmaps, expectations.

- Autonomy: Provide choices, delegate decisions.

- Relatedness: Show interest, create team rituals.

- Fairness: Be transparent, consistent, and inclusive.

We all share these needs but differ in how much we value each one—and in how we want them fulfilled.

Ask others about their needs, and share your own. It opens up new ways to prevent or resolve misunderstandings.

And remember: you can’t always meet every need. But being aware of them helps identify the root of many conflicts and accelerates resolution.

Learn More: Conflict Management Training

Conflicts may be unavoidable—but unresolved conflict doesn’t have to be.

Our Conflict Management Training helps you:

- Understand conflict dynamics and common biases

- Improve communication and reduce escalation

- Strengthen your leadership through empathy and clarity

👉 Explore our Conflict Management Training